Ten years of measurement

I tracked a huge panel of variables about myself for years, bringing me motivation and perspective on various health journeys. Over time I came to realize the things I measured were not the main story, they're more like a running commentary on the larger changes in my life.

Something

Measuring the body

As a teenager, I was fit and rake-thin, but in my mid-twenties my body began changing. At first, the extra weight I put on brought compliments. "Are you working out? You look buff." But then it continued, and it was clear that I'd need to put some effort into being healthier. At one point, I measured my waist, and realized I'd entered an at-risk category for diabetes, which horrified me into action.

Ultimately I managed to come back to a healthy weight by doing three things: I used a mobile app to track everything I ate, and limit my daily calories; I began walking to and from work each day, about 50 minutes each way; and I made a pact with several friends to lose weight for a wedding a few months out. Each of these things -- diet, exercise and social commitment -- are known to be effective and important. Years later this let me joined a weight loss company, confident that their product worked, and full of insights into people's everyday struggles.

During this process, I ended up capturing a ton of data on my eating habits, exercise and body measurements. Data mining all this did teach me about my body and habits, but not all the conclusions were exciting. They included things like: "when you eat margarine, you also eat bread" and "when you eat curry, you drink beer". Groundbreaking stuff.

This was the time of quantified self, and I began tracking other things, like my location, curious as to what I could learn. At that time I checked the entropy of my location data. Depressingly, one single bit of information was enough to determine my location with very high probability: I was either at work or I was at home.

From body to mind

Huge changes happened in my life over the coming years. My wife developed an aggressive form of brain cancer, fought it off successfully for some years, then unsuccessfully as it resurged and became too difficult to treat. I spent a year caring for her at home, and when she passed away, I followed the plan we'd made together and moved to Sweden to start afresh.

There I joined a health company, and my daily work became trying to make sense of vast swathes of diet and exercise data for our customer's benefit. But myself, I became increasingly convinced that the mental side of things was the main game. I began experimenting with different meditation practices, and tracked that, as a means of checking my progress.

I began devouring research papers about well-being in all its forms. I discovered the PERMA model of happiness, which breaks it down into multiple facets: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment. By doing a regular PERMA inventory and recording my scores, I learned that most aspects of my happiness were pretty stable. Sometimes a life event would spike or dip all facets together, but often just one facet would change, which gave me an extra angle for reflection.

Claiming what's mine

After the European GDPR legislation became enacted, getting data from companies became easier, but it also encouraged a totally different way of thinking about product usage. I began thinking about that data as mine, not theirs; occasionally I actually asked for it if I thought it was interesting.

Have you had Google Timeline enabled over a long period of time? Do a data takeout, now you have your location dataset. Use Goodreads as your reading queue? Request your data, now you know every book you started and finished. Actually download your data from Apple Health, Withings, Fitbit or whoever else keeps it. It's yours.

Despite doing this, I still become frustrated. I'd like to see the GDPR "right to access" your data become even stronger, with companies obliged to expose it via API to you, or available by daily automated export. Very few companies volunteer to do this, instead they give you once-off dumps. I'm sympathetic, it's a lot of work to create these APIs and maintain them. But it's very tiresome to ask for your data and have it come back to you "within a month". Right now I'd say we have the right to take our data and leave, but not the right to continuously access it if we stay.

Ten years of data

So, you assemble a wide and varied dataset on yourself, and maintain it over a long time period. After all that, what can you actually learn?

The truth is, even with a lot of data, even with good tools, it can be hard to get the insights you want. Often you can't interepret it well, since you don't have reference data for the rest of the population. This leaves you with only past versions of yourself to compare to. At other times, you want to tease apart the complex causal structure of habits, routines, and mental states, but a deep analysis is frankly less interesting than just experimenting with yourself and trying new things.

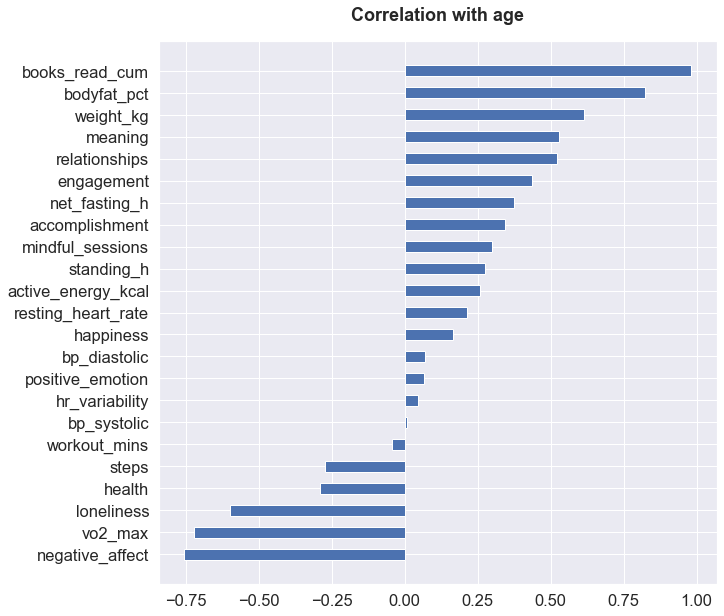

At other times, you shake the tea leaves and peer into a correlation matrix, curious to see if you missed something. A slice of my personal metrics gives me a plot like this:

Correlation matrix

The more you look for, the more random noise comes up, so we should firstly take these correlations with grain of salt. Secondly, these variables are not measured for the same spans of time, so each relationship is measuring a different intersection of weeks over the last 10 years; this also add noise. But, where we have reasonable priors beliefs to constrain things, we can still make some sense of it.

What kinds of things are correlated with getting older, for me:

Correlation with age

Two interesting themes that emerge, common to the broader population.

My health has declined over time, especially shown by increased weight and lower VO2max and increased resting heart rate. This is true for people in general; it's the normal experience of getting older. Some of these aspects of health get worse for everyone; for others I can "break" the correlation simply by working at it. After all, it's a log book, not an oracle for the future.

On the other hand, measurements of my mental life have improved across the board. I self-report a greater sense of meaning, richer relationships, a stronger sense of engagement, and reduced negative emotions like loneliness and anxiety as I grow older. Each of these are things I've noticed, and honestly they're a welcome change.

Invisible currents

Aside from whole-of-life trends, the smaller lessons are quite elusive. We looked at a great number of metrics earlier, and found some suggestive patterns. But these patterns are just correlations, they don't reveal the causal nature underneath.

XKCD correlation

For example, I became less lonely with age. But actually, I only began tracking feelings of loneliness after the death of my long-time partner, moving to an entirely new country where I didn't know anyone, and being far away from old friends. Since then, I developed new and deep friendships, changed jobs three times, met my current wife, got married, had our beautiful son, and taken up Stoic exercises to shift my perspective. Is it fair to look at all that and say "it was the passage of time that changed how you felt?"

In many ways, the causal structure of life is too complex and shifting to unravel into a few metrics. It's led me to believe that "nuggets of true insight" are few and far between, even on a highly meaningful and personal dataset like this.

A recommended path?

Having recorded all this, would I recommend that you too keep measurements over all aspects of your life? For most people, I would not.

Recording a lot of things about yourself can be an effective way of tackling an acute problem in your life. It can give you two insights: how bad is this problem, and what angle could I try to overcome it? The whole process brings with it a sense of control. But in reality, after initial findings, you face quickly diminishing returns. Sometimes we even know the actions we must take, but just haven't built up motivation or an environment supportive enough to actually do them.

One special reason you might choose to track is if, like me, you have interests in data science and health. In that case, you can get something different out of it all, in that you can ethically measure and experiment with yourself in a way that you cannot with other people. In the process you might gain insights that can help others on their own journeys, and the worst case is an increase in your data science skills.

Today, whilst I still collect personal data, I rely as much as possible on things being automatically tracked for me. Every week or two I "harvest" these into a central location for myself and see what's changed. My current fascination relates to how core beliefs and personality traits change over long time periods, so the little manual tracking I do is around periodically capturing these aspects of my mental life.

I'd love to hear other people's stories. Have you also tried measuring yourself for a long time? Shoot me an email and let me know how it turned out.